React.js Server Functions with Builder Pattern

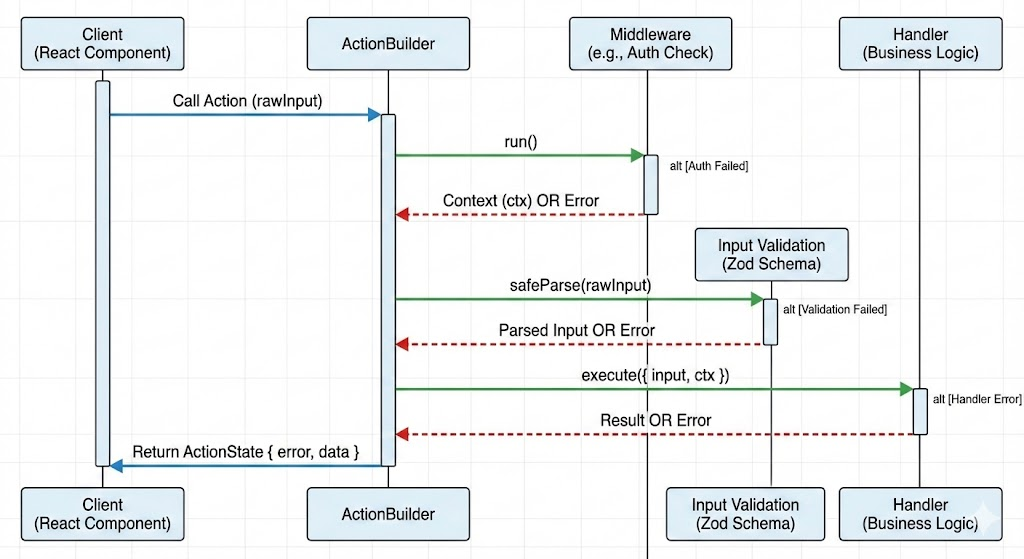

A walkthrough of how to use composable builders to standardize authentication, validation, and error handling in React.js Server Functions (Next.js Server Actions).

The Problem with Raw Server Functions

React Server Functions (or Server Actions) are an interesting addition to the ecosystem, further extending the principle of composability and recyclability of React by allowing us to call backend logic directly from our components. This eliminates the need to have a separate backend service that acts as a backend-for-frontend.

However, as an application grows, “raw” server actions often lead to code duplication, if not inconsistency due to the lack of any opinionated architecture around them.

You might find yourself repeating the same three patterns in every single action:

- Authentication: Checking

if (!session) throw Error. - Validation: Manually parsing input with Zod.

- Error Handling: Wrapping everything in

try/catchblocks to return UI-friendly error states.

To solve this, we can borrow a concept popularised by libraries like tRPC: The Builder Pattern.

The Solution: A Type-Safe Validation-Ready Action Builder

By creating a chainable ActionBuilder, we can define a pipeline that handles

middleware (like Auth), input validation, and execution context automatically.

1. Building the Core Class: Step-by-Step

Here is the heart of the system: ActionBuilder.ts. This class leverages

TypeScript Generics to ensure that as you add middleware, your context (e.g.,

user, session) is strictly typed and available in the final handler. Let us

break it down piece by piece. The goal is to create a chainable API where types

flow automatically from one step to the next.

A. Define the Return State

First, we need a standardized response format. This ensures our frontend code

never has to guess the shape of the response—it is either a success with data

or an error with a message. Let us normalizes the return type into a

predictable ActionState<T>.

type ActionState<T> =

| { error: true; message: string; data: null }

| { error: false; message: string; data: T | null };B. The Class Skeleton

Next, let’s scaffold the class. We need two pieces of state to travel with us through the chain:

TContext: The data we have gathered so far (e.g.,{ user: User }).TInputSchema: The Zod validation rules we will eventually run.

class ActionBuilder<

TContext = Record<string, unknown>,

TInputSchema extends z.ZodType = z.ZodVoid,

> {

// The constructor is private because we only want to create

// instances via our chainable methods.

private constructor(

private readonly middleware: () => Promise<TContext>,

private readonly inputSchema: TInputSchema

) {}

}❓ Why TInputSchema defaults to z.ZodVoid? In TypeScript, generic types

often need a starting value. If we didn’t set a default, or if we set it to

z.ZodType (a generic parent class), TypeScript wouldn’t know what the input

arguments should look like for a brand new builder.

By using z.ZodVoid, we tell TypeScript: “By default, this action takes no

arguments.” This allows us to write simple actions without calling .input() at

all. If we didn’t have this default, every single action—even simple

ones—would force you to define an empty object schema like

.input(z.object({})), which is tedious.

C. The Entry Point

We need a way to start the chain. We use a static factory method that returns a pristine builder with an empty context and no input validation.

class ActionBuilder {

// ...

static build() {

// Starts with an empty object context: {}

// Starts with a void schema: z.void()

return new ActionBuilder(async () => ({}), z.void());

}

}D. Adding Middleware

This is where the power of the Builder pattern shines. When we add middleware

(like authentication), we don’t just modify the current object; we return a

new ActionBuilder with an expanded type.

We use TypeScript intersection (&) to merge the old context with the new one.

class ActionBuilder {

// ...

use<TNewContext extends Record<string, unknown>>(

middlewareFn: (prevCtx: TContext) => Promise<TNewContext>

): ActionBuilder<TNewContext & TContext, TInputSchema> {

return new ActionBuilder(async () => {

// 1. Run the previous middleware to get base context

const prevCtx = await this.middleware();

// 2. Run the new middleware

const newCtx = await middlewareFn(prevCtx);

// 3. Merge them together

return { ...prevCtx, ...newCtx };

}, this.inputSchema);

}

}❓ Why is Middleware () => Promise<TContext>? At the constructor above, we

defined TContext to be wrapped in a Promise, and now we look at the reason

why. The middleware function returns a Promise because authentication is

almost always asynchronous. When you check if a user is logged in, you usually

have to: read a cookie, verify a session in the database and fetch

roles/permissions—all of which are async to various degrees. If our

middleware signature was synchronous (just () => TContext), we would be unable

to await those database calls. By typing it as Promise<TContext>, we ensure we

can perform necessary I/O operations (like checking auth session) before the

action runs.

E. Defining Input

Before we run the action, we usually need to validate arguments. The input

method allows us to swap the default z.void() schema for a specific Zod object

(e.g., checking for a lessonId). Notice how this updates the TInputSchema

generic:

class ActionBuilder {

// ...

input<S extends z.ZodType>(schema: S): ActionBuilder<TContext, S> {

// We keep the existing middleware, but replace the schema

return new ActionBuilder(this.middleware, schema);

}

}F. The Execution

Finally, we implement the method that actually runs our logic. This is where we combine everything: we run the middleware, validate the input, and then execute the developer’s handler.

Crucially, we wrap the whole thing in a try/catch block to ensure we always

return our predictable ActionState.

class ActionBuilder {

// ...

action<TOutput>(

handler: (args: {

input: z.infer<TInputSchema>;

ctx: TContext;

}) => Promise<TOutput>

) {

return async (

rawInput: z.infer<TInputSchema>

): Promise<ActionState<TOutput>> => {

try {

// 1. Run Middleware (Auth, etc.)

// This builds the 'ctx' object

const ctx = await this.middleware();

// 2. Parse Input (Validation)

const parsed = this.inputSchema.safeParse(rawInput);

if (!parsed.success) {

return {

error: true,

message: parsed.error.issues[0].message,

data: null,

};

}

// 3. Execute the actual Business Logic

const result = await handler({ input: parsed.data, ctx });

return {

error: false,

message: "Success",

data: result ?? null, // If the result is void, we coalesce to null

};

} catch (e) {

// 4. Global Error Handling

let errorMessage = "Unknown error";

if (e instanceof Error) errorMessage = e.message;

else if (typeof e === "string") errorMessage = e;

console.error("Action Error:", e);

return { error: true, message: errorMessage, data: null };

}

};

}

}❓ What is happening at the function signature? Notice the rather

complicated part at the start of the action method. This specific part of the

code is the “bridge” where TypeScript connects the configuration (Validation +

Auth) to the actual business logic.

action<TOutput>: This Generic defines what the function returns. We almost never define this manually. TypeScript infers it automatically from the handler’s return statement.z.infer<TInputSchema>: This is the magic that gives us typed inputs. It looks at the Zod schema you passed into.input()earlier and converts it to a TypeScript type.ctx: TContext: This ensures your handler has access to all data gathered by middleware.TContextis the accumulated type of everything returned by your.use()calls.=> Promise<TOutput>: This enforces that the handler must be asynchronous. Since Server Functions run on the server and usually talk to a database, forcing aPromisereturn type prevents synchronous blocking code.

In short: This signature tells TypeScript: “The function I am about to write will receive the exact input I defined in Zod, the exact context I defined in Middleware, and whatever I return will determine the output type of the API.”

G. The Full Class

// ActionBuilder.ts

import { z } from "zod";

type ActionState<T> =

| { error: true; message: string; data: null }

| { error: false; message: string; data: T | null };

class ActionBuilder<

TContext = Record<string, unknown>,

TInputSchema extends z.ZodType = z.ZodVoid,

> {

private constructor(

private readonly middleware: () => Promise<TContext>,

private readonly inputSchema: TInputSchema

) {}

static build() {

return new ActionBuilder(async () => ({}), z.void());

}

use<TNewContext extends Record<string, unknown>>(

middlewareFn: (prevCtx: TContext) => Promise<TNewContext>

): ActionBuilder<TNewContext & TContext, TInputSchema> {

return new ActionBuilder(async () => {

const prevCtx = await this.middleware();

const newCtx = await middlewareFn(prevCtx);

return { ...prevCtx, ...newCtx };

}, this.inputSchema);

}

input<S extends z.ZodType>(schema: S): ActionBuilder<TContext, S> {

return new ActionBuilder(this.middleware, schema);

}

action<TOutput>(

handler: (args: {

input: z.infer<TInputSchema>;

ctx: TContext;

}) => Promise<TOutput>

) {

return async (

rawInput: z.infer<TInputSchema>

): Promise<ActionState<TOutput>> => {

try {

const ctx = await this.middleware();

const parsed = this.inputSchema.safeParse(rawInput);

if (!parsed.success) {

return {

error: true,

message: parsed.error.issues[0].message,

data: null,

};

}

const result = await handler({ input: parsed.data, ctx });

return {

error: false,

message: "Success",

data: result ?? null,

};

} catch (e) {

let errorMessage = "Unknown error";

if (e instanceof Error) errorMessage = e.message;

else if (typeof e === "string") errorMessage = e;

console.error("Action Error:", e);

return { error: true, message: errorMessage, data: null };

}

};

}

}

export const buildAction = ActionBuilder.build;Addendum: Why Auth runs before Validation

You might notice in the action method that we await this.middleware()

before we parse the input with Zod.

// 1. Run Middleware (Auth)

const ctx = await this.middleware();

// 2. Parse Input (Validation)

const parsed = this.inputSchema.safeParse(rawInput);We do this for three reasons:

- Security (DoS Protection): Validation (especially with Regex or large arrays) is CPU-intensive. By authenticating first, we ensure that resources are only spent on valid users. If an unauthenticated attacker sends a malicious payload, we reject it before wasting CPU cycles parsing it.

- Preventing Information Leakage: Validation errors are often descriptive (e.g., “Password must be at least 8 characters” or “Role must be ‘ADMIN’”). If validation runs first, unauthorized users can probe your API to deduce your database schema or internal rules. By running Auth first, unauthorized requests receive a generic Unauthenticated or Forbidden error, keeping your internal data structure opaque.

- Context-Aware Validation: Sometimes, validation logic depends on the user context (e.g., checking if a user has permission to edit a specific id). By running middleware first, we ensure ctx is available if we ever need to move complex validation logic into the schema.

2. Defining Base Procedures

Instead of rebuilding the auth logic every time, we define “Procedures” (similar to tRPC). This creates a reusable base for different levels of access control.

In actionProcedures.ts, we create a protectedProcedure that guarantees a

user exists in the context. If the session is missing, it throws an error

before the action handler is ever reached.

// actionProcedures.ts

import { getUserSession } from "lib/auth/authFuncs";

import { buildAction } from "./ActionBuilder";

// Base procedure: no auth required

export const publicProcedure = buildAction();

// Protected procedure: enforces Auth

export const protectedProcedure = publicProcedure.use(async () => {

const session = await getUserSession();

if (!session || !session.user) {

throw new Error("Unauthenticated");

}

// This return value is merged into the context (ctx)

return { session, user: session.user };

});

// Admin procedure: enforces a specific role

export const adminProcedure = protectedProcedure.use(async ({ user }) => {

// We have access to 'user' here because we chained off protectedProcedure

if (user.role === "ADMIN" || user.role === "SUPERADMIN") {

return {};

}

throw new Error("Forbidden");

});✨ Build it up the way you want it: You can really build and chain however

many .use you like and however granular. You can even put specific handlers

into specific procedures, such that the relevant functions are available in the

context.

3. Usage: Writing Clean Actions

Now, writing a server action becomes incredibly clean. We don’t need

try/catch, we don’t need manual validation, and we don’t need to check for the

user—TypeScript knows the user is there.

Here is an example of a lesson completion toggle. Notice how ctx.user.id is

fully typed.

import { z } from "zod";

import { protectedProcedure } from "./actionProcedures";

export const actionToggleLessonCompletion = protectedProcedure

.input(

z.object({

lessonId: z.string().min(1).max(120),

courseId: z.string().min(1).max(120),

})

)

.action(async ({ input, ctx }) => {

// 'input' is typed from the Zod schema

const { lessonId, courseId } = input;

// 'ctx.user' is guaranteed by protectedProcedure

const { user } = ctx;

// Some database or I/O work

await dbCreateOrDeleteUserProgress({

lessonId,

userId: user.id,

});

// Revalidate cache here if you use any

// Whatever is returned here becomes part of the data payload

// whilst the message field is set as "Success"

return "User progress updated";

});ℹ️ In a future article, we will discuss Next.js caching and ways to make our lives easier there as well.

4. Client-Side Consumption

Because our builder wraps the return in ActionState, our frontend components

can easily handle the response.

// Example Component

"use client";

import { useTransition } from "react";

import { actionToggleLessonCompletion } from "@/actions";

export function LessonCheckbox({ lessonId, courseId }) {

const [isPending, startTransition] = useTransition();

const handleToggle = () => {

startTransition(async () => {

const result = await actionToggleLessonCompletion({ lessonId, courseId });

if (result.error) {

toast.error(result.message);

} else {

toast.success("Progress saved!");

}

});

};

return (

<input

type="checkbox"

disabled={isPending}

onChange={handleToggle}

/>

);

}🌱 Next steps: The logic of handling action states can probably be encapsulated into a hook!

Summary

This pattern provides a robust foundation for React.js and Next.js applications:

- Type Safety: Input and Context are inferred automatically.

- Security: Authentication is handled in one place (the procedure middleware).

- Consistency: All actions return a standardized { error, message, data } object.

- Clean Code: Business logic remains focused, separated from plumbing code.

If you want to see this code in action, check out the sPhil repo 💾.

I’m also developing this and trying things out as I go, so I welcome any ideas and suggestions for improvement.

© Filip Niklas 2024. All poetry rights reserved. Permission is hereby granted to freely copy and use notes about programming and any code.